Photo: Osprey, Lewis Scharpf/Audubon Photography Awards

Evelyn Novins

It’s always a joy when Osprey return to northern Virginia in the spring to breed after their winters in the Southern Hemisphere. Like the Bald Eagle, the bird is a prime example of successful population recovery following the ban of DDT, increasing in Chesapeake Bay from 1,450 pairs in the 1970s to 10,000 nesting pairs today, about ¼ of the population in the United States. So, it’s disheartening to learn of an increase in nest failure in areas of the Chesapeake Bay, reported by both Greg Kearns, senior naturalist for the Patuxent River Park, and Dr. Brian Watts, from the Center for Conservation Biology at William and Mary University.

Osprey, Kurt Wecker/Audubon Photography Awards

But before we dig into that discussion, let’s review a little information about the Osprey, Pandion haliaetus, sometimes called the fish hawk, seahawk, or fish eagle. It’s a diurnal bird of prey which hovers over water before making spectacular dives for fish. It spots the fish from as far as 150 feet up and begins a forward dive to the water, but it enters with its feet first to grab the prey. Its nostrils close to keep out the water, and a nictitating membrane protects its eyes. The Osprey’s talons have a 6- to 8-inch spread and are equipped with spicules (spiky spines) to grasp its catch securely. Holding the fish head forward as it flies back to the nest, it usually stops along the way to eat the head first, killing the fish and stopping its struggle. It appears that 1 in every 3 or 4 dives is successful.

Osprey traditionally build their nests at the top of tall trees. However, they have become accustomed to and look for man-made platforms which suit them well. They seem to know that their primary predator, racoons, find these structures difficult to raid. However, the great horned owl and the eagle still have access. Ospreys exhibit nest fidelity, returning to the same nest site year after year, especially if they have been successful in raising chicks. First year Osprey often remain on wintering grounds for an extra year before heading north to breed in the area where they were born.

Back to reports of nest failure at high levels in certain areas of the Chesapeake Bay. First, note that a nest productivity rate of 1.15 or greater is required to sustain a population. Greg Kearns, who has been monitoring Osprey along the Patuxent River for 40 years, reports a drop in nest productivity from 1.8 in 2013 to 0.86 in 2024, or 6.57% nest failure in 2013 to 45.07% in 2024. Even higher levels of nest failure were reported in some intervening years: 58.95% in 2017, 60.41% in 2020, and 56.67% in 2023, productivity rates of 0.73, 0.67, and 0.61, respectively. Kearns’ March 18 talk, Ospreys on the Patuxent, a Smithsonian Environmental Research Center presentation and the source of those figures, is still available online free of charge following registration.

Dr. Watts’s research of Ospreys in the Chesapeake Bay indicates that Osprey feeding in lower salinity areas in the rivers appear to be doing better than those Osprey near the middle of the Bay, the main stem of the Chesapeake with its brackish waters. The diet of river Ospreys consists of gizzard shad and catfish while the diet of Ospreys in the main stem of the Chesapeake is 75% menhaden.

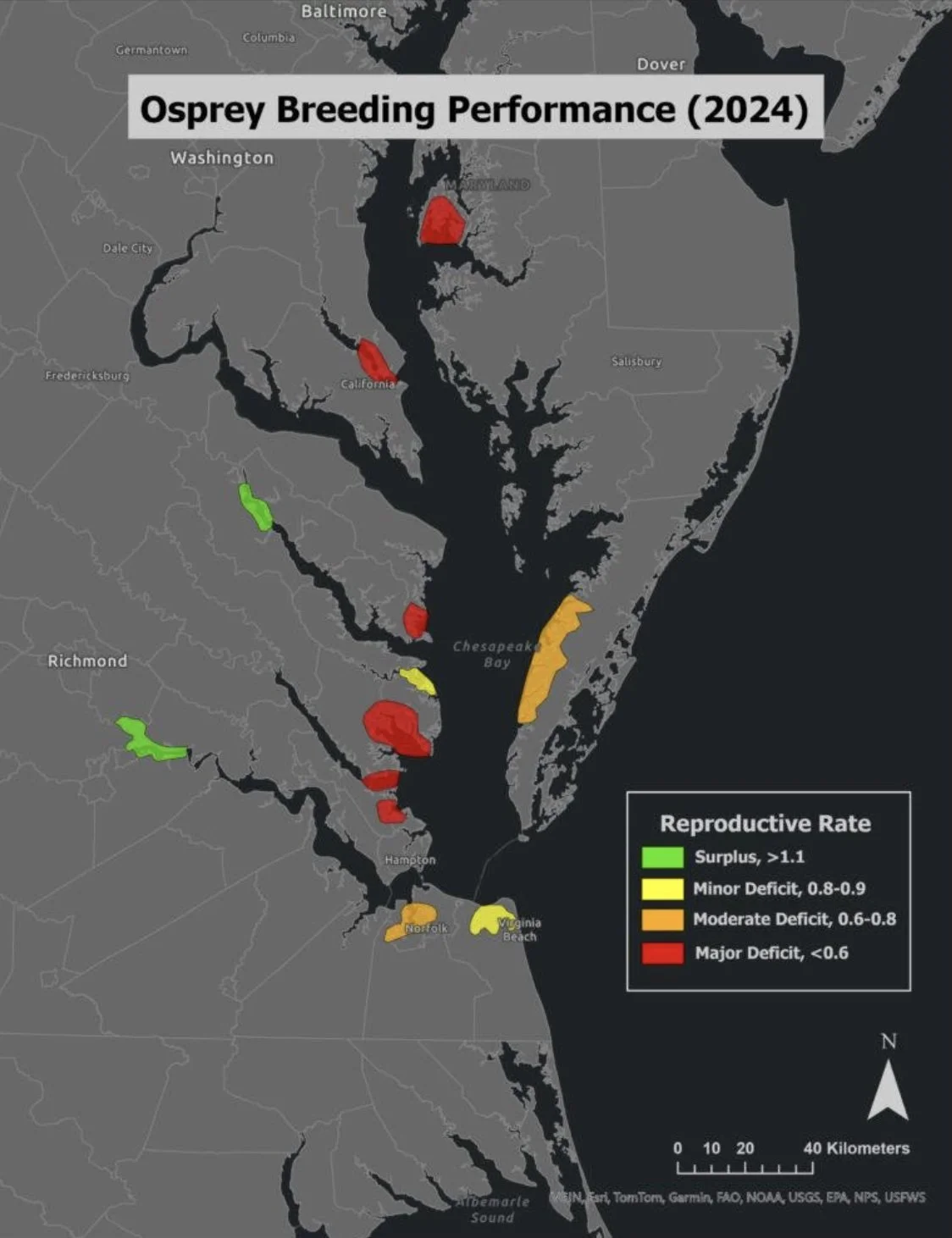

An Osprey breeding performance map from an article by Dr. Brian Watts shows areas of steep decline.

He reports that mean breeding performance for Osprey pairs nesting within the main stem of the Bay did not meet the productivity rate required for population maintenance. The reproductive rate in this area was 0.51 young/pair in 2024. The cause of nest failure, documented through webcams, nest inspections and necropsies of dead chicks, is starvation. Dr. Watts’s article on poor breeding performance of Chesapeake Bay Osprey is available here. A graphic from his article shows areas reporting steep declines.

Conservation groups have urged protections to prevent overfishing of menhaden in the Bay, and the fisheries industry has pushed back. Regulation of the industry in this area is by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission in Virginia’s waters, and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, which monitors stock assessment. Menhaden spawn in the Atlantic and swim into the mouth of the Bay, with the Bay becoming a menhaden nursery, where they live for several years before returning to the Atlantic to spawn.

Menhaden is a nutrient-rich fish containing a very high concentration of protein and omega-3 fatty acids. It is also the primary food source for Chesapeake Bay Osprey and striped bass (rockfish), an iconic Chesapeake Bay fish, which is in decline. Humans don’t consume menhaden, but it is a target of the reduction fishery, which reduces it to a protein-rich fish meal, a commodity used in salad dressing, pet food, omega-3 supplements, oils, makeup, pellet food, and other products.

Conservation and sport fishing organizations argue that the area is being overfished, disrupting its ecological balance and causing the increasing rate of Osprey nest failures and decline in striped bass. The menhaden industry is an important one in Virginia, and it has pushed back.

In 2024 the Chesapeake Legal Alliance, with the Southern Maryland Recreational Fishing Organization and other organizations, submitted a petition for rulemaking to the Virginia Marine Fisheries Commission urging regulation of menhaden fishing in Chesapeake Bay and the reduction fishery. After receiving 1,325 comments, the Commission decided to take no action.

Two bills to authorize a three-year study of the ecology, fishery impacts, and economic importance of the Atlantic menhaden population in Virginia’s waters failed in the 2025 General Assembly, HB19, a proposal introduced by Delegate Lee Ware in 2023, and HB2713, introduced by Delegate Paul Milde in 2025. It’s likely that the issue will return in the 2026 session, in January 2026. We all need to support collection of the necessary scientific information to determine how best to balance the needs of conservation and industry. It’s not too early to send a letter to your representative in the General Assembly urging support for a similar bill in 2026.